·Fanis Michalakis · fiction · 13 min read

Bitterfly

Hidden deep in the meanders of a sophisticated script was the information that the press clamoured for and only an experienced metroologist could unveil.

“Metroology, from greek metroo (the ledger) and logos (the study), refers to the study of the ledger, and what is found within. Its practice requires a certain conformation of the mind, which…” – Extract of the Universal Encyclopedia

He was instantly met by the wind when he stepped outside. A cold breeze climbed up Belmer Street, carrying dust, salt, and the scent of the sea. Adjusting his coat, Croissal crossed the street and descended into the subway. His discussion with Lady Lowry lasted longer than he had planned, and he was late for his next appointment. He should have cancelled this meeting with Lowry. Dealing with fretful wives and cheating husbands was part of the job — some months, a substantial part of the job — but, at the end of the day, all cases looked the same. The next one, a homicide, was far more promising. Stay professional, said the voice in his head. A man is dead.

The underground transportation system whisked him two districts away. He returned to the surface, emerging in a vast plaza filled with trees.

The wind was gone, and so was the fragrance of the sea. He headed east, walked a few minutes, and finally found himself in front of 67 Crescent Alley.

A woman in her twenties came to the door when he rang. Her eyes were lost in a distant gaze, her hair gathered in a messy bun. She managed to produce a faint smile as they shook hands. “Mr. Croissal, thank you for coming. I’m Claire Hebnar, Mr. Hebnar’s daughter.”

She showed him into a cosy living room and asked if he would drink anything.

“Tea. Black. Thank you, Miss Hebnar.”

As she went to the kitchen, Croissal cast his eyes on the room around him. The decor was sober but elegant, successfully mixing the very en vogue minimalistic style of abruptalism with touches of traditional oriental furnishing. A few books and a candle were aligned on the low table before him, mimicking the perfect order in which opulent tapestries and rosewood furniture alternated against the wall.

When Miss Hebnar came back with the hot drinks, he thanked her. And, after a quick and ceremonial expression of his condolences, he jumped straight to the point.

“Did your father have any enemies?”

Of course, he did. So many she couldn’t even start to list them. All of them due to his profession. In his private life, Bab was a very quiet man, always trying to avoid conflict, and respected and loved by his friends, family, and neighbours. But what he did for a living inevitably created tensions with some people, many of whom were wealthy enough to put a juicy contract on his head.

“He was assigned public protection, you know? His talents were recognized enough that the mayor had two men of the City Watch protecting him and this house. It’s one of them who found the body. He had not seen my dad for the whole day and was worried when he didn’t answer the door. They did their own investigation to try to find who could have gotten in here and, well, killed him right under their noses, but they didn’t find anything. I’m not a believer, Mr. Croissal, not in any kind of gods or spirits at least, but they said it’s just as if a ghost came and took him. They’re reluctant to close the case because it all happened on their watch, but I think they’re at a complete loss. Hence why…”

“Hence why you called me, Miss Hebnar.” He interrupted gently. “Can you think of a way someone could have snuck in unseen? Concealed doors aren’t too uncommon in these old houses.”

She shook her head. “No. the house blueprints indicate an old passage, but it was walled up decades ago by the previous owner.”

Croissal nodded. “I understand your father’s body was found in his offce? His exploration room, is this what it’s called? Would you mind if I took a glance at the place?”

Claire Hebnar smiled — the same faint smile that she greeted him with — and acquiesced. Leaving the living room, they walked down a long hallway, until they were met by a tall metallic door. Looking at it, Croissal expected the door to be heavy, but the young lady pulled it open with only one hand and no apparent effort. Probably a special alloy. Not so thick, not so heavy, but highly insulating.

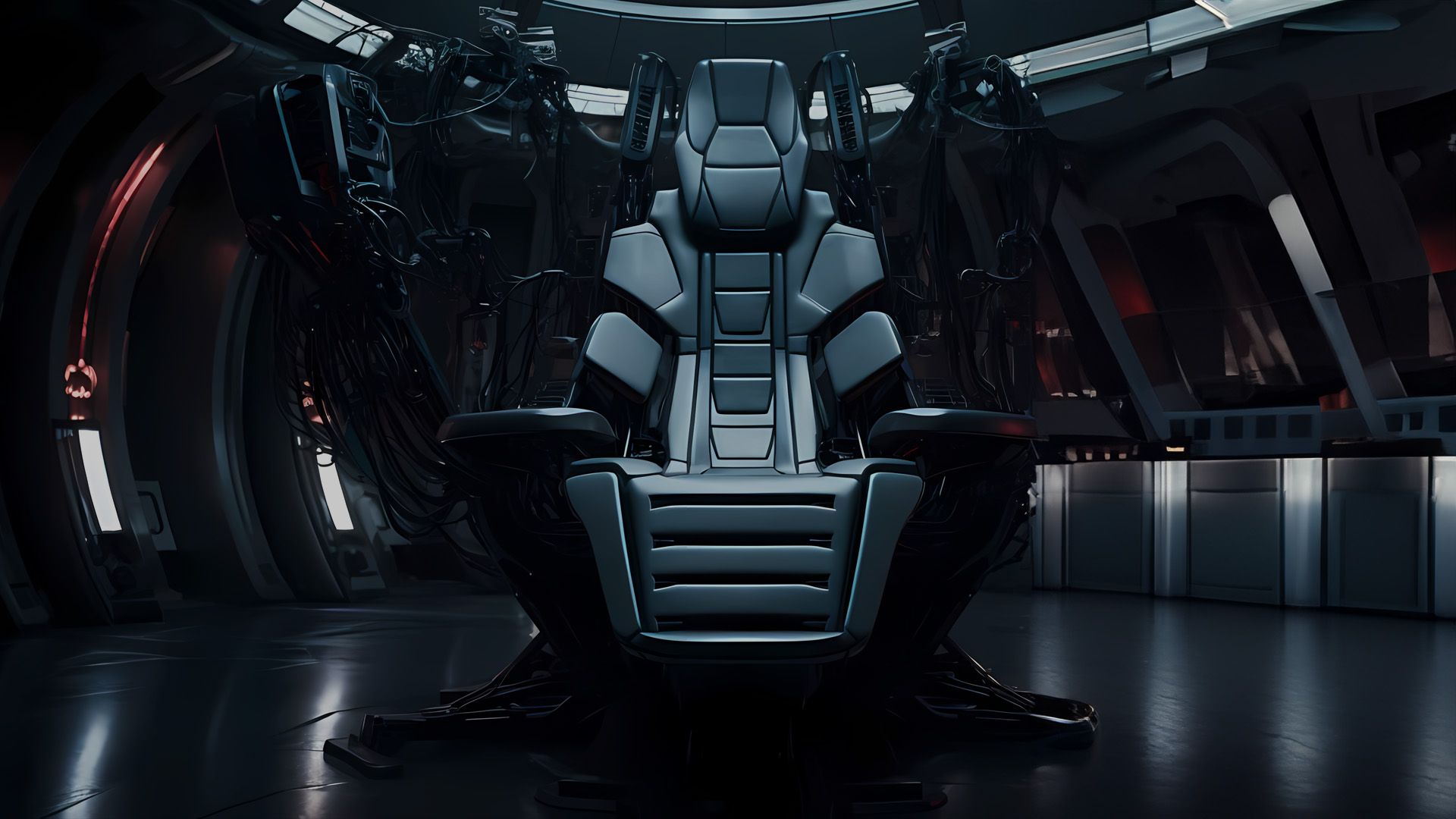

The room itself appeared smaller than he expected. What looked like a huge orthodontic chair surrounded by curved panels hanging from the ceiling occupied the middle of the room. Three of the four walls hid behind racks of servers, whose hum, however muffled, filled the room with a faint background noise.

“They found him in his chair, the daughter said. The interface was turned off, but he used to take naps there sometimes. I think he liked the sound of the computers.”

Croissal hardly heard her. Breathless, he stared at the chair and its apparatus, looking as if he had witnessed an apparition.

“Is this … Is this the device he used to … read it?” he murmured. Miss Hebnar laughed slightly, half-amused, half-bitter.

“Yes. They call it an MLI, Man Ledger Interface. But Bab called it the chair. The panels are all around your head when you’re sitting inside, and together, they cast some kind of hologram. You’re literally inside the ledger, and there are those little commands on the armrests.” She pointed with her finger. “The operator uses them to move the stream around themselves. I’ve never quite understood how it works, but I’ve seen my dad use it since I was a little girl. When I was a kid, I used to watch as he disappeared inside a blueish mist, both mesmerized and startled, unable to move until he emerged hours later, having extracted the precious answers that important people sent him looking for.”

“Was your father working on something specific lately?”

“No. He had just published his findings in the Rev Case a few weeks ago. You must have heard about it in the news. Since then, he had been waiting for his next mission.”

Croissal had certainly heard about the Rev Case. It pitted the two heirs of the deceased President of the Rev corporation, Henry O’Cal, against each other. Who would be the new head of the company? The man had left no clear will, and the authorities had no choice but to turn to metroologists to try to identify the deceased’s intentions through the tangle of contracts and transactions registered for eternity on the ledger.

The case had made tremendous noise because of the sums at stake. Rev was an old corporation, with its roots dating back to only thirty years after the Genesis, back when people still called the ledger “bitcoin.” Rev was active in virtually every aspect of the economy. Knowing which child would inherit the company was on everybody’s mind. And now Salim Hebnar, the man who provided a desperately needed answer — here in favour of the daughter, if he recalled correctly — was dead.

As was the custom and the law, Hebnar had disclosed his findings publicly, highlighting exactly what led him to reach his conclusions. Croissal dug into his memory, trying to remember what evidence the metroologist had put forward in this specific case. There was something about a thirty-year-old transaction, the early days of Henry O’Cal’s presidency. And something even more ancient — a decision made by one of the early members of the company’s board. Hidden deep in the meanders of a sophisticated script was the information that the press clamoured for and only an experienced metroologist could unveil.

Seeing control of the company slip through his fingers, O’Cal’s son appealed the decision. With no luck. Was it enough to motivate murder?

Croissal’s head was starting to hurt a bit, his blood pulsing in perfect rhythm against his cranial cavity. He must have been lost in his thoughts for some time because Miss Hebnar stared at him, visibly worried.

“Yes, I’ve heard about this case.” He mumbled, remembering the young woman’s last sentences. “What was your father doing while he waited for a new client?”

“The Rev case had been quite exhausting, so he rested for a few weeks. That’s what he usually does — did — so nothing particular, in case you’re wondering. Then, when he felt refreshed, he used to do some research on his own.” She paused, looking at the machine in the centre of the room. “He really liked that, you know. Digging through traces of the past, like a digital archaeologist. Not trying to solve a specific dispute, just looking for worthwhile relics. For the sake of it, not for money. That’s what he liked the most, I believe. He could spend the whole day in the chair, travelling from transaction to transaction. Solving cases for clients was just a way to finance all that.”

“So,” interrupted Croissal, counting the weeks, “your father was probably working on his own research when he was killed.”

“Yes, probably. I’m not sure. I wasn’t living with him anymore.”

Interesting, Croissal thought. But not helpful. He already had a list as long as his arm full of potential murder suspects, starting with O’Cal’s son. Now, he had to add other unknown names to this enumeration: Could the metroologist have found something he wasn’t supposed to during his wanderings inside the ledger?

They went back to the living room. Thoughts raced through Croissal’s head. He somehow managed to take leave of Miss Hebnar and head back to his office, a few districts away. He decided to go on foot. There was something about the rhythmic motion of walking that helped him clarify or untangle his thoughts. Right now, his mind was a labyrinth, and he desperately needed a way out. His journey took him through Stillman’s Street, famous for harboring many alcohol distilleries during Prohibition nearly a century ago. Many buildings had concealed windows through which men could buy their poison. When Prohibition was repealed, and the alcohol shops closed, the name endured.

Croissal paused. Something felt off, as if he knew he was missing a piece of a puzzle he hadn’t even started yet. Surely, taking some time to reflect on this in his office wouldn’t hurt. He resumed his walk, his mind racing faster than his feet, eager to reach the familiar confines of his building.

When he entered the small, impersonal room, he immediately noticed the files in the middle of his desk. His assistant must have received the Hebnar record from the City Watch and put it there. He sat down and went through the papers.

Body found at around 9 pm (…) lying in the MLI (…). Death most probably caused by the absorption of a high dose of hemlock…

Croissal grinned. The autopsy had revealed a high concentration of poison found in Hebnar’s system, so high that one would have thought the cause of death was beyond doubt. But the City Watch was a very old institution, proud of its procedures that could drive any sane being to insanity. It was why private eyes like him were needed. Just in case.

The autopsy found that the hour of death was probably between 2 and 4 pm on the same day the body was discovered. (…) The vector through which the poison was injected into the victim’s digestive system remains to be found. No trace of hemlock was found in any food or drink at the house of the victim.

Suddenly, something clicked in his mind. The autopsy placed the time of death between 2 and 4. Hebnar was in his research phase, between two jobs, where he could spend the whole day on his chair. He was found in the chair. And yet, the interface itself was turned off. There was something he had to check — on site, in Hebnar’s office — and quickly.

Croissal grabbed his coat and stormed out of the building. It had been lying there, right under his eyes, since the beginning. The events were not crystal clear yet, but if he was right… He had the feeling he was on track to find something monumental.

He got there as quickly as he could. Hebnar’s daughter looked surprised and displeased with his unannounced visit, but telling her he had something to check regarding her father’s death was enough to remove her objections. She left him alone in the office, and he started searching, his fingers exploring the many cracks running along the server racks. Finding nothing, Croissal turned to the massive chair in the middle of the room.

He wasn’t sure what he was looking for, but it had to be here. Nobody could have come in and out without the men of the Watch noticing — no secret passage. Mr. Hebnar was preparing his own meals, precisely out of fear of poisoning. It was literally the impossible murder, except for one specific person.

His fingers groped the underside of the chair. There! A small and thin rectangular shape. Slowly, he removed it. A memory chip. He pressed the small button at the centre of the device, and a delicate screen unfolded and opened like a lotus. Once it had fully bloomed, the screen lit up, and Salim Hebnar’s face appeared in the middle. He looked agitated but determined.

I have uncovered a terrible thing. I’ve been to places where none of my contemporaries should ever set foot. Down to the foundation of it all, and everything we stand upon is a lie. A lie! I shouldn’t have gone there. But I had to. I thought my role was to seek truth … Oh, my dear Claire, was I wrong!

The truth is nothing but chaos. I’ve seen the point of inception. The initial set of defining conditions. It’s a forgery. Our whole society is based on a forgery. I wish the ledger could lie, but I know it can’t. It’s alien to our need for stability. It’s a pendulum set in motion by our own madness, and now only our lies can protect us from its storm.

Croissal’s eyes were glued to the screen, his breath suspended.

There is only one way through this. I am so sorry, Claire. I hope you will understand. I did this for you. To protect you. You are all I ever truly loved. I take the unspeakable truth with me. No one must ever know. It’s … I have to stop this. The… flap of a butterfly’s wings shouldn’t have such consequences.

Claire… I love you, forever.

The screen went black. During the final seconds, Hebnar’s voice reduced to a murmur; his face twisted into a strange rictus. But there was no trace of madness in his eyes. Only the flame of a cold resolution.

Croissal looked over his shoulder. The door remained shut, and he was alone in the room. He broke the device into pieces and slipped the fragments into his coat pocket.