·Anonymous writer · fiction · 13 min read

Shiro

SANTIAGO, CHILE (AP) — An American military jet slips in from the sea, past the grim old monoliths that ring Rapa Sat Island and roars to a short, dusty stop on the new airstrip.

SANTIAGO, CHILE (AP) — An American military jet slips in from the sea, past the grim old monoliths that ring Rapa Sat Island and roars to a short, dusty stop on the new airstrip.

Molish Moari dashes out of his pink stucco house and mounts his motorbike. “My butter is on that plane!” he yells. “Tonight we’ll have butter for the corn and lobster!” Excitement erupted throughout the village of Hangaroa, where nearly all of Easter Island’s 1,500 mostly Polynesian inhabitants live.

The lobster feast celebrates a new discovery on Rapa Sat; a 48–foot–tall ancient monument has been discovered on the island and the locals are brimming with questions.

Dr. Shiro Wakaranai of the Otis Institute of Archaeologists and his team have been excavating on Rapa Sat since January. While other symbolic structures have been discovered during that time, there has been nothing this grand in scale and character. “We discovered a rectangular granite post and assumed that digging deeper would uncover more of the same,” said Dr. Wakaranai, “Imagine our surprise to discover the post floating above the soil, suspended in mid-air.”

The team nicknamed the giant discovery simply “the Sat” in honor of the island. While the find is authentic, the reason for its construction remains a mystery. The team dates the Sat to around 4000 B.C.

(continued on pg. 4)

What is particularly interesting about this story—besides the giant floating stones—is that it’s not in any public record. In fact, this particular newspaper edition was never actually published. Why? And how does a regular guy who paints murals for a living know all this? Because I’m the one who found this newspaper.

Last January, 2176, I was hired to paint an animated mural at Álvarez Fusion HQ in Lincoln, Nebraska. I later discovered the building previously belonged to The Post Globe newspaper c.1955 to 2004. This job was already behind schedule. Once on-site, we discovered the size of the mural wouldn’t fit on the lobby wall without hitting a 90-degree return. Animated murals tend to glitch at corners and get worse over time, so for this job, the client needed to tear out the corner and add two extra meters of straight wall to accommodate the mural. The BuildBots made a racket all around me as I worked.

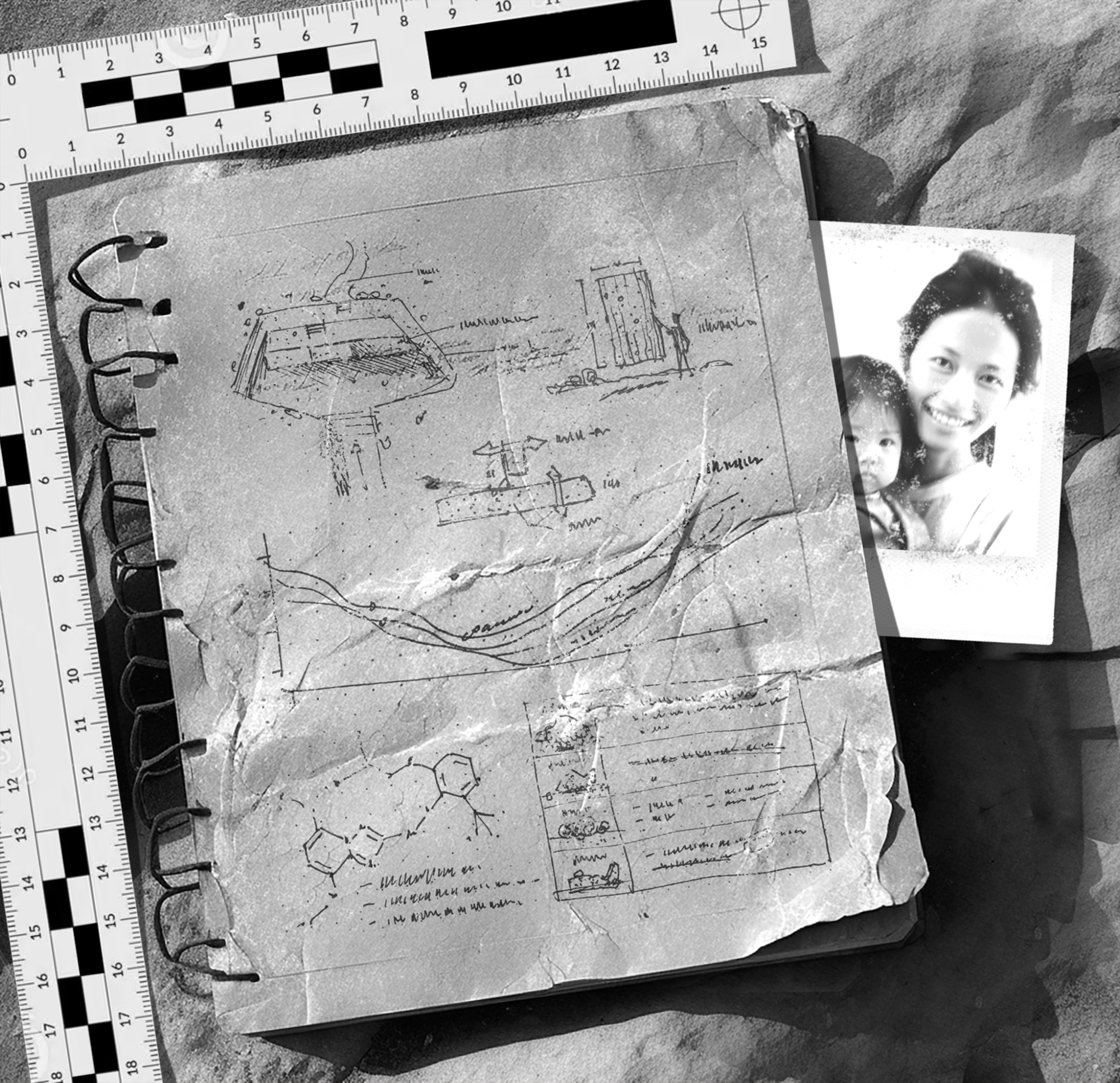

One evening, after the bots powered down and I was packing up for the night, I saw a roll of paper peeking out of a destroyed wall. A newspaper! It must have been stuffed in the wall during the original building construction. I had never actually touched a newspaper before. They can be worth quite a bit, and this one wasn’t in bad shape. On the front page was the article about “the Sat” discovery. Next to the article was an incredible picture of giant stone slabs, weighing tons, seemingly floating in the air above an excavated hole in the ground. I had never heard of it. No one had ever heard of it. Lev tech was less than thirty years old, so nothing could have levitated 200 years ago. This must have been a gag, possibly a novelty newspaper printed one time as an inside joke between a group of pranksters.

I pressed the SeeRing on my finger and made a query: “Dr. Shiro Wakaranai, Otis Institute of Archaeologists.” An image materialized of an affable-looking young man of Japanese descent, disheveled and in need of a proper haircut. He looked more like a ragged ditch digger than a scrupulously groomed man of science. To the right of his picture appeared his name “Dr. Shiro Wakaranai, MA, RPA, Assoc. Professor of Archeology, UNO. Born January 3, 1951, died August 11, 1976,” and then a brief but unremarkable record of his life and work. He died young. In fact, he died shortly after discovering the monument on Rapa Sat. What should have been a scientist’s magnum opus was glaringly absent from his bio.

II

The University of Nebraska, Omaha, I thought, that’s not too far from here. I pressed the ring again and said, “Dr. Shiro Wakaranai, present lineage starting 1976.” An arrow materialized across my field of vision, drawn from left to right. More faces appeared starting with his wife Melissa Fields (née Wakaranai), a celebrated philanthropist. She lived well into her eighties. The next line revealed their only child, Dr. Michael Wakaranai, MD, PhD, Head of Pathology at Stature Health. He and his wife had three children. The line broke apart and became many lines; they blossomed into scores of fractal groupings. More lives, all connected to Dr. Shiro Wakaranai. More names followed by many professional credentials. Dr. Wakaranai would’ve been proud of his progeny. There were a lot of smarts in this family tree.

“Pause,” I said around the fourth and fifth generations. Although my entire view was now filled with thousands of names and faces, one name stood out to me. I pointed my finger and gently spun my ring with my thumb to zoom in closer. “Deb Colleymore, Senior Scientist, Staheli Sciences. Born 2146.” Hmm, we’re almost the same age, I thought. Staheli Sciences. I’ve seen that somewhere before. I know that name from somewhere.

It didn’t take long to figure out. ‘STAHELI SCIENCES’ were the giant words floating around a red tower adjacent to my hotel. The tower had been framed quite nicely by my west-facing window. Though clearly seen, it never piqued my interest until now. From then on, when I looked out the window, I saw nothing else.

Too many coincidences I thought. Deb Colleymore, the Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Granddaughter of Dr. Shiro works right there. The universe was screaming for me to take another step. I pressed my ring. “Is Deb Collymore listed?”

The SeeRing returned, “Deb Colleymore is not listed.” I didn’t sleep well that night.

The subterranean entrance to the Staheli building was directly across from the coffee shop where I was now sitting. I had been in this spot since 6:30 am, smelling cappuccinos and croissants while my line of sight was floating just above the sidewalk sign that read, “Hey girl, how you bean?” Every employee of Staheli Sciences had to pass directly by me before they reached the front doors leading to their workstations inside. It didn’t take long before the morning rush moved past me like a flood. I stood to get a better view of each passing face hoping I wouldn’t miss her. What if she had cut her hair short? What if she dyed it from sandy blonde to some other color? What if she’s on vacation? But then she made her appearance. She looked exactly like the picture I saw the day before. She stood out, walking tall with purpose while others around her were distracted absently consuming the morning news or chatting away on their See.

I leaped forward into the crowd making my way towards her but having no idea what I was going to say. “Excuse me. Deb?” I would try to sound like a colleague. I was too timid and the noise of the crowd was not helping. There was a clearing in the flow of the crowd which would get me to within a meter of her so I juked through it. “Miss Colleymore!” I said louder than I meant to.

She jumped and turned toward me wide-eyed, her hands raised in quasi-self-defense. “I’m sorry,” I said quickly. “I didn’t mean to scare you.”

She stayed rigid, except for a subtle turn of her head, her eyes still on me.

I stumbled and stammered trying to explain my existence. I was a muralist… the wall demolition… the newspaper… the name of her company. It all sounded so disjointed; she didn’t wait for me to get to the point. “Oh, okay. Hmm, well I must be going,” she said as she turned her back on me and hurried towards the entrance making a beeline to the uniformed security guard standing just inside the doors.

“Shiro Wakaranai is in that newspaper!” I yelled.

She stopped in an instant. All at once, the last of the commuters seemed to drain away, and the space around us suddenly became empty and quiet as a church. She turned around. “Say that again.”

I held up the newspaper that was at my side, the picture of the Sat immediately grabbing her attention. She walked slowly back towards me.

III

The people of Lincoln moved via underground tunnels in the deep winter. They were cozy but crowded tunnels. It was not an ideal place for private conversation without distraction so we agreed to meet later that evening on Prairie Plains, an elevated park directly above my hotel. El-parks are spread out, warm, and shielded with enough protective energy that we could meet high above the city skyline even in the middle of the freezing Nebraska winter. It was public, but we could talk privately.

Deb was a pretty lady. She had green eyes and was professionally dressed. She wore a cream-colored business jacket along with a flowy orange scarf that swayed comfortably past her shoulders. I thought she looked more like a business executive than a scientist. She looked younger than me even though she was three years my senior. Working mainly on building sites like I do can age you prematurely. I could tell she wasn’t a field scientist, unlike Dr. Shiro. As we sat on a secluded bench near the edge of the park, She held the newspaper gently with both hands, pouring over the article and the photo again and again, smiling all the while. Then she turned her eyes to meet mine, eager to listen to the details of my find.

When I asked if she had known about the Sat monument before her eyes no longer darted around playfully; she became present. She locked onto my eyes and stayed there for a while.

She said “Yes, I know all about this. My family holds Shiro in very high regard. He’s left quite a legacy. How this article was printed and then successfully buried, however, is a complete mystery to me.” Her expression softened, as if a long-held breath was finally released from deep in her chest. She put her hand on my arm, “I’ll share it with you. It’s time I think. You already know the beginning, you might as well know it all.”

Rapa Sat, 1976. Dr. Shiro Wakaranai climbed up the ladder that was leaning on the lowest slab of the Sat and walked out of the excavation site. His small Datsun truck nearby had his water canteen on the front seat, and he was grateful to have a taste. He sat down in the driver’s seat and pondered the stone slabs through the truck windshield with muddy wiper streaks, visualizing those streaks as a primitive measuring caliper to playfully gauge dimensions on the Sat.

Lately, he preferred to work alone. He would rather discuss precise measurements and mass using state-of-the-art tools that he had ordered from the institute, but all his peers wanted to talk about was their imminent fame. The locals only wanted to talk about the riches tourist dollars would surely bring to the island. Shiro wanted none of it. His curiosity about anthropology and archeology had always been insatiable. He just loved digging. He imagined every handful of dirt brought him closer to mankind and every significant find broadened his understanding of humanity. He had survived Vietnam only to return to violence here at home. Shiro thought of war as an absolute absurdity and so did the voice.

Three weeks ago, Shiro heard a whisper in his ear - a murmur both old and kind coming from the ancient stones. The voice wasn’t speaking a known language, but Shiro could understand it. It wasn’t making a sound, but Shiro could hear it, sometimes in his ear other times through his chest. He couldn’t explain it, so, like any good scientist, he asked questions. The voice provided answers.

On August 11, 1976, the day he reportedly died, Melissa Wakaranai received a letter from her husband. On that day the colossal Sat simply fell to the ground without warning. Shiro, who was working in the pit below, was killed instantly. No one else was injured, but the Sat was in ruins, broken apart, returned to the Earth as shattered rock. In the letter Shiro spoke of understanding the Sat, explaining that it wasn’t an inanimate object at all, but more of a sentient force. He wrote about the voice. He could not say if it was theological, extraterrestrial, or even magical, all he knew was it was good. It spoke of old truths and universal knowledge that would benefit billions all over the world. He wrote about his own death, predicting the monument would fall back to the earth and be buried forever and him with it. Its purpose was done while his purpose was just beginning.

Deb Colleymore had a scan of that letter now floating between us.

“Only my body will be gone.” the letter read. “I’m not useful to the world as Shiro Wakaranai the archeologist. I’m too small, too human. I will share knowledge anonymously. I will speak as different people through time, planting world-changing ideas for the good of humanity. Ideas passed on from this wisdom of unknown origin.

“I profess my eternal love to you, Melissa. Know that I will be with you and Mikey forever through time, watching lovingly. You will know when I am near, it will be impossible to miss. No matter what happens I remain your devoted husband and Mikey’s proud father.”

When Deb saw that I was through reading the letter she closed the See file and looked back down at the old newspaper between us, her eyes brimming with tears. We sat in silence for a few minutes while I digested everything.

“So,” I finally said, “over the last 200 years, these anonymous discoveries…?”

She nodded. “Jawahir Mirza?” I asked. She answered, “…Gave us cures for the world’s most devastating diseases, nobody knows who they are, and they haven’t been heard from since 2080.”

“Guy Brisbois?”, I questioned.

She replied, “The anonymous architect of a balanced justice system.”

“Mateo Álvarez?”

“—Gave us a blueprint to harness the Sun… unlimited energy. He holds no patents. We don’t know who he was.”

“Mei Li!” I blurted out “revolutionized food distribution, then… ”

“Poof,” finished Deb.

Who else? I wondered.

“Satoshi Nakamoto,” she said, “created our monetary system that freed us from financial subjugation. That was his first persona, back in 2009. Melissa and Michael had known it was Shiro because of the name: Satoshi… Sat. It had to be him. Each great contribution given freely, each great discovery or idea passed through an anonymous figure. That’s Shiro,” she said proudly.

We sat in silence for a while. She fished in her purse for a tissue. I shifted in my seat to look at the clear night sky through the gently pulsing energy field, a technology made possible, coincidentally, by Mateo Álvarez.

“Now you know,” she said, lightly touching the newspaper next to me. “Are you ok?”

I thought about it for a moment. “I think I am.”

She nodded then stood up. Three hours had passed. She put her hand on my shoulder and thanked me. Then she turned and began to walk away.

“Your newspaper,” I said, lifting it toward her.

She smiled at me and said, “Finders keepers,” then left me there. Alone with the stars. They were bright.