·Guilherme Bandeira · blog · 12 min read

So, where is everybody? How Bitcoin solves Fermi Paradox

Roughly eighty years ago, physicist Enrico Fermi and his colleagues pondered the existence of intelligent life beyond ourselves.

Roughly eighty years ago, physicist Enrico Fermi and his colleagues pondered the existence of intelligent life beyond ourselves.

Contemplating our success story here on Earth, they also thought about the immensity of the galaxy, with 100 billion stars, how life evolved so quickly on this planet, and that an intelligent species like ours would likely colonize other places in the galaxy in just a few thousand more years. Paleontology shows us that organic life evolved very quickly after the Earth’s surface cooled and became habitable. Once simple life existed, evolution through natural selection showed progressive trends towards sexual reproduction, larger bodies, bigger brains, and social complexity. Evolutionary psychology reveals several plausible paths from simpler minds towards the creative intelligence of humans. If this was possible on Earth, extraterrestrial intelligence should be common and abundant, given the number of other planets that exist. Enrico Fermi listened patiently to the digression of his esteemed physicist colleagues and then asked:

“So, where is everybody?”

This enigma became known as the Fermi Paradox.

Over time, the paradox became increasingly intriguing. After it was proposed, hundreds of exoplanets were identified, which could indicate the presence of habitable planets orbiting various stars relatively close to us. However, decades of intense searches for extraterrestrial intelligence have yielded nothing. No radio signals have been sent back to us, no close encounters beyond sparse and unreliable reports.

So, it seems there are two possibilities. Perhaps we are overestimating the probability of the evolution of extraterrestrial intelligence. Maybe the conditions that made intelligent life possible here on Earth are much more unique than we imagined, even with so many planets out there. Or perhaps evolved intelligence has some profound tendency to self-limit or even self-exterminate. After we invented atomic bombs, some suggested that any alien intelligent enough to create spaceships would also be intelligent enough to make thermonuclear bombs and would use them against each other sooner or later. We are alone because any extraterrestrial intelligence also self-destructs in one way or another.

Recently, I read a different, also grim, solution to the Fermi Paradox. Evolutionary biologist Geoffrey Miller proposed that intelligent aliens did not self-destruct through some super technology they eventually invented. They simply became addicted to different virtual realities or metaverses that intelligent life inevitably creates. They don’t need Sentinels to enslave them in a Matrix: they do it to themselves, just as we are doing today.

For Geoffrey, evolutionary biology shows us that even an evolved mind is drawn to indirect signs of biological fitness rather than tracking fitness itself. In our evolutionary history, we did not seek reproductive success directly; we sought tasty foods that tended to favor our survival and attractive partners who tended to produce cute and healthy babies. Since we only seek signs and not the thing itself, we are easily drawn into addictions and virtual worlds.

Technology produced by our intelligence is very good at controlling external reality and promoting our true biological fitness in different niches of the Earth, but it is even better at offering false fitness cues, imitations, and subjective signals of survival and reproduction without lasting or healthy effects in the real world, like candy and pornography. A juicy and nutritious piece of meat is more costly to obtain than a cereal bar full of flavor additives. Having real friends or a wife requires much more effort than watching Friends or subscribing to OnlyFans. Building rockets and colonizing the galaxy is much harder than playing Star Wars video games and settling for a simulacrum of these activities.

We are in this trap because technology that only imitates evolutionary fitness tends to progress much faster than our psychological resistance to it. Today, generations already reach adulthood immersed in a lush world of entertainment that imitates evolutionary fitness, while the traditional elements of physical and mental development, such as maintaining a healthy body, building a family, and leaving a legacy, which were fundamental to our perpetuation and civilization, are left aside.

This trend directly impacts the economy and production. At the beginning of the last century, most inventions still referred to physical reality that actually improved people’s lives on Earth, such as cars, airplanes, zeppelins, electric lamps, vacuum cleaners, air conditioners, bras, and zippers. Today, most inventions concern virtual entertainment and conspicuous consumption. We have already shifted from a reality-based economy to a virtual economy, from physics to psychology, as the engine of value and resource allocation.

Geoffrey wrote about this hypothesis in 2006, at the beginning of this detachment. Today, we see in the concentration of the stock market a deep accentuation of this trend. The world’s top three companies, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple, which have surpassed an incredible USD 3 trillion in market value and together dominate 20% of the S&P 500 index, have business models directly linked to the creation and monetization of virtual realities. This is not to mention other huge companies like the trillion-dollar Meta and Netflix, which is now worth almost USD 300 billion.

Geoffrey’s hypothesis is that perhaps intelligent aliens have met a similar fate. In the evolutionary history of any intelligent life, there will arise what he called the Great Temptation: they will also be given the ability to mold their subjective reality to provide evolutionary fitness cues without the real substance.

Perhaps we are following the same path as intelligent alien species and gradually extinguishing ourselves, allocating more time and resources to virtual pleasures and less to the healthy construction of future generations. The demographic results of this indicate almost irreversible trends, with signs of population collapse in countries like South Korea and Japan.

For Geoffrey, the only evolutionary escape from the Great Temptation is some kind of bifurcation in humanity that will emphasize the values of hard work, delayed gratification, and child-rearing. In this bifurcation generated by hereditary variation, a portion of humanity will understand the dangers of the Great Temptation and know how to avoid it. They will develop a horror of virtual entertainment, psychoactive drugs, and contraception. The generations that survive in the future will be forced to curate the world of entertainment and our metaverse economy strictly. If eventually, some grand encounter occurs between us and intelligent alien life, the much-dreamed-of Contact, it will certainly not be a meeting of beings addicted to virtual entertainment. It will be a meeting of zealous and very serious parents who congratulate themselves for having survived not only the atomic bomb but also the metaverse.

Although Geoffrey’s hypothesis is plausible, it is at least incomplete. We don’t need advanced technology to create a virtual reality; it is enough for any intelligent life to have some rudimentary knowledge of chemistry or botany to cultivate and synthesize their own drugs capable of creating parallel universes that imitate evolutionary fitness. The ritualistic use and control that traditional cultures and religions already have over certain drugs is a sign that social rules have been selected and transmitted for the controlled use of various substances, certainly out of the atavistic fear of the long-term destructive potential they have for the individual and society. As Geoffrey himself acknowledges, the hereditary variation of cultures can develop resistance to the Great Temptation, so it is only a matter of time before we develop greater resistance to technologies that do this as well as to drugs we have known for thousands of years.

But the basis of his hypothesis may still be correct: that intelligence itself contains the seeds of its own limitation or destruction. It is quite possible that today entire sectors of society are consumed by imitations of evolutionary fitness, which give us false cues of success before we can develop resistance to them, and that this causes deleterious effects until we find some solution that creates incentives to get us back on track for real development. What is missing for his diagnosis to be more complete is to apply this reasoning to something more fundamental in the economy and society: money. Money is half of every economic transaction, establishes the terms of trade, and regulates our relationship between value and time, so no analysis will be complete without knowing the destructive capacity of a bad monetary paradigm to create illusions similar to the imitation of evolutionary fitness.

Any intelligent species anywhere in the universe will also have to develop a form of money to facilitate their economic exchanges and make use of the distributed knowledge that only a market based on free monetary exchanges can make. Therefore, the question of what material can serve as a monetary good and form the basis for the market that may eventually have arisen among them will also be raised for aliens.

All intelligent life, besides being powerful enough to create a virtual reality through the imitation of evolutionary fitness, will also be able to extract or even create chemically or physically any element they may find. In general, this is great if we consider capital goods and consumer goods. It means that productivity is increasing. It would be great for alien life to develop advanced technology to extract from their own planet and others easily and cheaply any material they needed, continuously progressing in Kardashev’s scales.

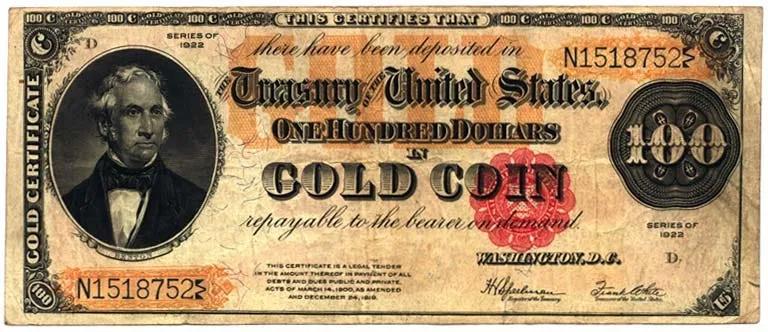

But this would be bad for the existence of a monetary good. The same power could be used to inflate the supply of any good used as money, and this will be a big problem for intelligent life, just as it has been for us. Gold has proven to be the most resistant good to our ability to inflate it, but even it could not prevent episodes of inflation when, for example, in the 16th and 17th centuries, a large amount of gold and other precious metals was extracted from the Americas and parts of Europe began to suffer from price increases due to the sudden increase in monetary supply.

In our economic history, gold was demonetized in the 20th century because it is costly to transport, so it had to be centralized in banks and gained scale imperfectly, in the form of credit, with promissory notes and bills. Once centralized in a few institutions, it was not difficult for governments to confiscate and break its backing from the metal. But one can imagine another end for gold as currency. Imagine a scenario where humans in the early 20th century had developed a technology capable of chemically creating gold extremely quickly, easily, and cheaply. The entire world would have suffered hyperinflation through technology. This would also have demonetized gold, and we would have to find another substitute.

Considering technological progress, any other alien life sooner or later will have to face this same problem. Any other life will have to escape the easy money trap (to use Saifedean’s Ammous term) created by their own intelligence and ingenuity. When we increase the supply of a monetary good, we are also creating the illusion that we have created something of value when, in fact, we are only diluting its purchasing power. Costless inflation is a type of virtual reality without real backing, creating the imitation of wealth, so we always seek the scarcest and hardest-to-inflate good to function as currency. Intelligent alien life will also have to avoid falling into this temptation of having a weak money, with episodes of inflation or hyperinflation, which would hinder their own development.

It is no mystery to anyone that since 1971, when Nixon broke the dollar’s gold backing, practically the entire world has been living on a pure fiat standard (with the honorable exception of Switzerland, which managed to maintain the franc’s gold backing until the 1990s before joining the IMF). Since then, we have globally felt the deleterious effects created by the virtual reality of fiat currency. Gold ceased to function as the natural regulator of the money supply, and central banks were free to artificially expand the amount of existing money without any cost.

Decades before Geoffrey’s sophisticated metaverse technology, society had already begun to feel the civilizational decline created by fiat money. On the website that compiles data on what happened after 1971, we see clear signs of regression, such as: 1. increase in families where both husbands and wives need to earn an income to support themselves; 2. increase in young adults living with their parents and unable to form their own families to levels not seen since the Great Depression; 3. increase in the average age of first marriage; 4. increase in the number of divorces at all ages; 5. increase in the number of single mothers.

These are just five indicators I selected to show the profound paradigm shift that was the lack of a strong monetary standard in family creation. On the same website, we find other graphs showing a strong correlation between weak money and the deterioration of social and economic indicators, long before videogames, streaming services, social media, or virtual reality glasses.

These facts indicate another possible solution to the Fermi paradox: intelligent life may be limited not only through the creation of the imitation of evolutionary fitness but also by the chronic absence of a monetary standard resistant to the inflation generated by technological success. If not for Bitcoin and the discovery of absolute monetary scarcity, we would be doomed to the economic and social decline we have seen since the 1970s and would never have a chance to colonize other galaxies.

Any successful alien life will have to, sooner or later, find something like Bitcoin, as they will be able to inflate any other element used as money. Perhaps intelligent extraterrestrial life is rare because, at some point in their development, they failed to overcome the inflationary disaster that comes with greater control over nature. Or, as Tomer Strolight proposes, Bitcoin is an extraterrestrial technology given to us by some benevolent alien who had already solved this problem. But this hypothesis is too implausible and speculative for my taste. I am inclined to think that Bitcoin is one of the great human creations that will save us from ourselves and that many of our colleagues in other galaxies were not as ingenious.

If you are interested in all the possible futures bitcoin might help develop you should buy your own copy 21 Futures!

Click on the cover or here to get it!