·Guilherme Bandeira · blog · 12 min read

The Eternal Beauty of Proof-of-Work

'Money is gold, everything else is credit' John Pierpont Morgan in 1912.

From the not-so-rare beauty of gold, to the rare beauty of Bitcoin

Money is gold, everything else is credit

John Pierpont Morgan in 1912.

Until the existence of Bitcoin, considering all the options selected in countless reiterated exchanges, gold was a natural element that best served as money. As (almost) everyone knows, this was due to the superior characteristics that gold has in relation to other materials and which are necessary for a monetary good to function properly: divisibility, portability, fungibility, durability, verifiability and, of course, high scarcity rate (stock-to-flow ratio).

But gold is not just that. Gold is also a very beautiful metal, which is apparently just a coincidence and a non-monetary characteristic.

Gold has a rare beauty among the class of metals, perhaps for this reason many people have confused its universally recognized beauty with mistaken notions such as intrinsic value. Add the universally shared desire to keep it or use it as an ornament on clothing, in palaces and churches, with its high scarcity rate, and an apparently perennial value is born. When this widespread desire meets limited supply, it becomes easy to fall into the illusion that gold has some kind of value in itself, something that would explain the incredible ability of this bright yellow metal to maintain value for millennia, although this is a metaphysical and economically wrong idea.

If at first glance beauty is not a monetary criterion, at a second glance it is clear that it is, at least, a proto-monetary criterion.

From Carl Menger in the classic On the Origin of Money (1892), through Ludwig von Mises in his famous regression theorem exposed in the seminal Theory of Money and Credit (1912), reaching Nick Szabo in Schelling Out (2002), everyone agrees that the first commodities that served as money were collectibles used as ornaments and that aesthetic criteria were important for their value and acceptance as a valuable asset to be exchanged between individuals and communities.

Shells were polished and bones were worked so that pre-Columbian Amerindian could have money in the form of jewelry, wedding gifts or legacies, and thus participate in reciprocal altruism between different tribes and generations. Those who received these “proto-money” expected that these beautiful objects could be exchanged for other goods later, this being precisely the origin of the indirect exchanges that constitute all monetary goods and an overcoming of both barter and forms of bilateral credit between strangers.

Several of these beautiful objects were tested with greater or lesser degrees of efficiency, but it was gold as a monetary technology that dominated in recent human history due to the superior characteristics mentioned above and also because the societies that adopted it prospered, managed to reduce their time preferences, knew how to save and invest. Whoever survived to tell the story survived because they knew how to use superior monetary assets.

It is no coincidence that, at the height of the gold standard, the so-called national currencies — the franc, the mark, the dollar — were not really national currencies as fiats are today. National coins on the gold standard were, conceptually, just cutouts of gold, with the very definition of money taking place within the scope of weights and measures, that is, different ways of cutting out the precious metal.

For example, the Gold Standard Act of 1900 stated: the US dollar consists of 25.8 grains of gold of 90% purity, as if there were no conceptual difference between the coin and the metal in these specifications and human convention was merely a form of cutting and measuring the purity of the metal, and not constituting ex nihilo, based on positive law, a government currency with legal tender, as fiat currencies are today.

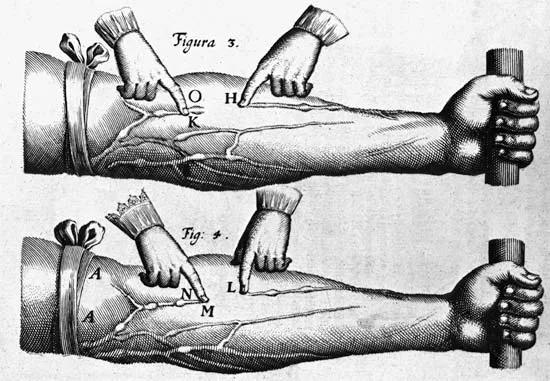

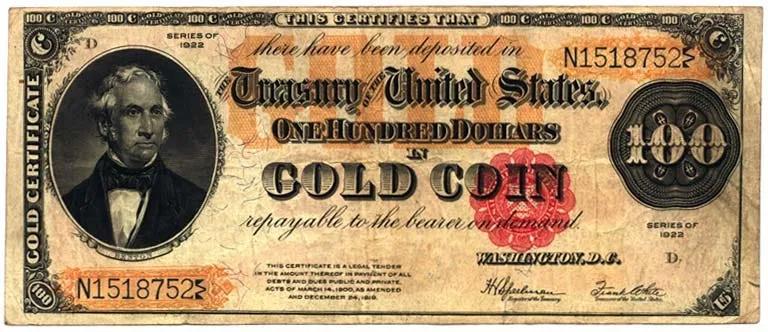

When we still respected natural laws in monetary matters, the banknotes that circulated in the economy were bearer instruments redeemable in a certain amount of gold deposited in the coffers, which were depositories of true money — only represented by banknotes in the form of credit. Although the historical emblems of that society were printed on these notes (monarchs, presidents, great legislators), the most important thing was the gold that backed them.

Look at this beautiful “100 dollar gold coin redeemable by bearer on demand” note issued in 1922 in the United States. Contradicting what all economists say, if the old J.P. Morgan mentioned in the epigraph of this text looked at it, he would say: that’s not money. He would say: “That image of the Honorable Sir Thomas Hart Benton on the note is very beautiful, but I’m sorry, this note is credit. Real money is that shiny yellow metal and the only one capable of providing final settlement on the gold standard”. In other words: not your vault, not your gold, not your money.

Several cultures have noted the geological improbability of the existence of gold in the crust of the Earth. But there is the geological history of gold, the human history with gold and the history of gold monetization, the latter much more recent than the first two.

We began to see the use of collectibles such as shells and tusk bones in the Upper Paleolithic, but it was only recently in the 6th century BC that Lydian kings like Croesus, innovators in the political art of seigniorage, decided to monetize gold, minting the first golden coins with their emblems. But this did not stop other physically and temporally distant cultures from trying to explain the apparently random existence of this rare metal in the Earth’s crust in the most varied ways.

In Western culture, gold was the emblem of Apollo, god of the Sun, and the ultimate goal of alchemists. In Inca mythology, the Sun, Apu Inti, was the source of all life, and gold, in turn, was its tears. An explanation, in fact, that is not entirely wrong, since gold is formed in nuclear processes in stars and is thrown across the universe in supernova explosions. The Incas said that Apu Inti created the first human beings, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, and sent them to Earth to begin civilization. To show his benevolence, Inti presented the Incas with gold, a divine gift, also a material manifestation of solar energy. If at some point in human history we decided to transform gold into money, it was a way we found to transform this condensed natural energy as a representative of the time and human energy necessary for the production of goods that we value for their usefulness. Fair. Value for value.

Even demonetized today under the fiat standard, gold, at least on paper, is still on the balance sheets of many central banks and also in the imagination of resentful and ignorant people. One of them is Mr. Flávio Dino, the Minister of Justice of the Brazilian government, who is still bothered by the fact that the Portuguese Crown has mined gold on Brazilian soil for many centuries — even before Brazil existed as a country — saying that Portugal should hand over the stolen gold. It is not the point here to unravel the historical and legal ignorance of the Honorable Minister of Justice — even if it is considered that it was a robbery, such a crime would already have expired and its perpetrators have been dead for many years.

The best response to the minister came from an accurate post by Felippe Hermes, who wrote:

Useless curiosity: the gold that Portugal took from Brazil in 300 years is the equivalent of what [the Federal Government in] Brasília took from the tax payer in the last 10 days (considering the current price and not historical conversion). The reason, of course, is that gold is far from scarce. In fact, production has grown by 2000% in the last 2 centuries, thanks to the advancement of technology. This means that Portugal took from Brazil in 3 centuries the same amount that the world produces in gold today every 15 days (in 2022 the world produced 3000 tons of gold).

That’s exactly it: at the current rate, what the Brazilian government collects from Brazilians per day is much more than Portugal took from Brazil in centuries. Resources, in fact, that come out of Brazilians’ pockets and go directly to financing Mr. Minister Flávio Dino’s salary.

Another fundamental point that is also in Felippe’s post: the supply of gold is elastic, that is, it responds to the price. If the price rises, there is an incentive to inflate its supply by mining even more gold and human beings are great at this, we are very ingenious beings when we have a strong incentive to do so. Today we are able to mine exponentially more gold than in the 18th century, when the gold rush actually began on Brazilian soil.

Therefore, instead of venting his resentment towards a friendly nation like Portugal, the minister should pay attention to the fact that a new gold rush 2.0 is taking place right now. with bitcoin mining, as I warned here more than two years ago. Brazil has enormous energy potential and would generate much more wealth if it started mining bitcoin, this is the best monetary asset that exists, truly scarce and why not, beautiful?

One day I was reading about the great Brazilian mathematician Artur Avila and I was surprised when I read about the importance of beauty in the role of his discoveries. The article said:

Thousands of ideas will occur to the mathematician throughout his productive life. Everyone says that the main criterion for immediately recognizing the superiority of those who stand out is the fact that they are beautiful. Mathematicians are closer to artists than engineers. “Imagine two entirely distinct things, created independently,” proposes Artur, “and imagine that, for some mysterious reason, you discover that they are part of one thing only.

He is describing one of the modes of the aesthetic sense, to which he is particularly sensitive.

The author of the article argues that Arthur’s aesthetic sense comes from the beauty of totality and his ability to bring ideas together, discovering unsuspected relationships between things, as if there were music that only mathematicians could hear and as if Arthur could put together seemingly incompatible melodies. Satoshi wasn’t a mathematician, but Arthur’s relationship with mathematics makes me wonder if Satoshi hadn’t also used an aesthetic criterion to create a type of rare beauty for issuing bitcoins.

It is known that Satoshi was not a great inventor in the area of cryptography and that he used existing tools such as SHA-256, Merkel Trees, etc., coding in C++ in a not very beautiful way. But let’s look at it from another aspect. The birth of the Bitcoin network was like the explosion of a digital supernova in which twenty-one million units — or, more precisely, 2.1 quadrillion sats — were launched into the realm of mathematical possibility, each with a strict timetable for their issuance.

The digital scarcity that Satoshi found is a beautiful scarcity, a mathematically beauty found in the confines of entropy limited by the nounces and achievable only by the proof-of-work. The issuance of new bitcoins are unique and at the same time eternal events, approximately every 10 minutes new bitcoins are found and placed in a successive chain of custody.

This idea was recently floated by none other than Adam Back, inventor of HashCash, who wrote:

While mined #bitcoin aren’t visual like a Picasso, they are unique like a snowflake under microscope. the leading 0s aesthetically pleasing, the statistical improbability, thermodynamic cost of finding them — it’s like computational art, a digital unqiue rare diamond to marvel at.

Finding gold in a mine also requires luck and work. But gold found in nature and deposited there by natural entropy needs a great deal of work not only to be found but also to be monetized. It needs to be purified, melted and go to some forge to acquire the fungible pattern of coin or ingot. Bitcoin, on the other hand, when it “leaves” nature, it is ready at the address of the miner who found it. From there it can be easily transported in a short time to any other address via communication channels (this property is explored by Satoshi himself discussing the Mises regression theorem that I mentioned above).

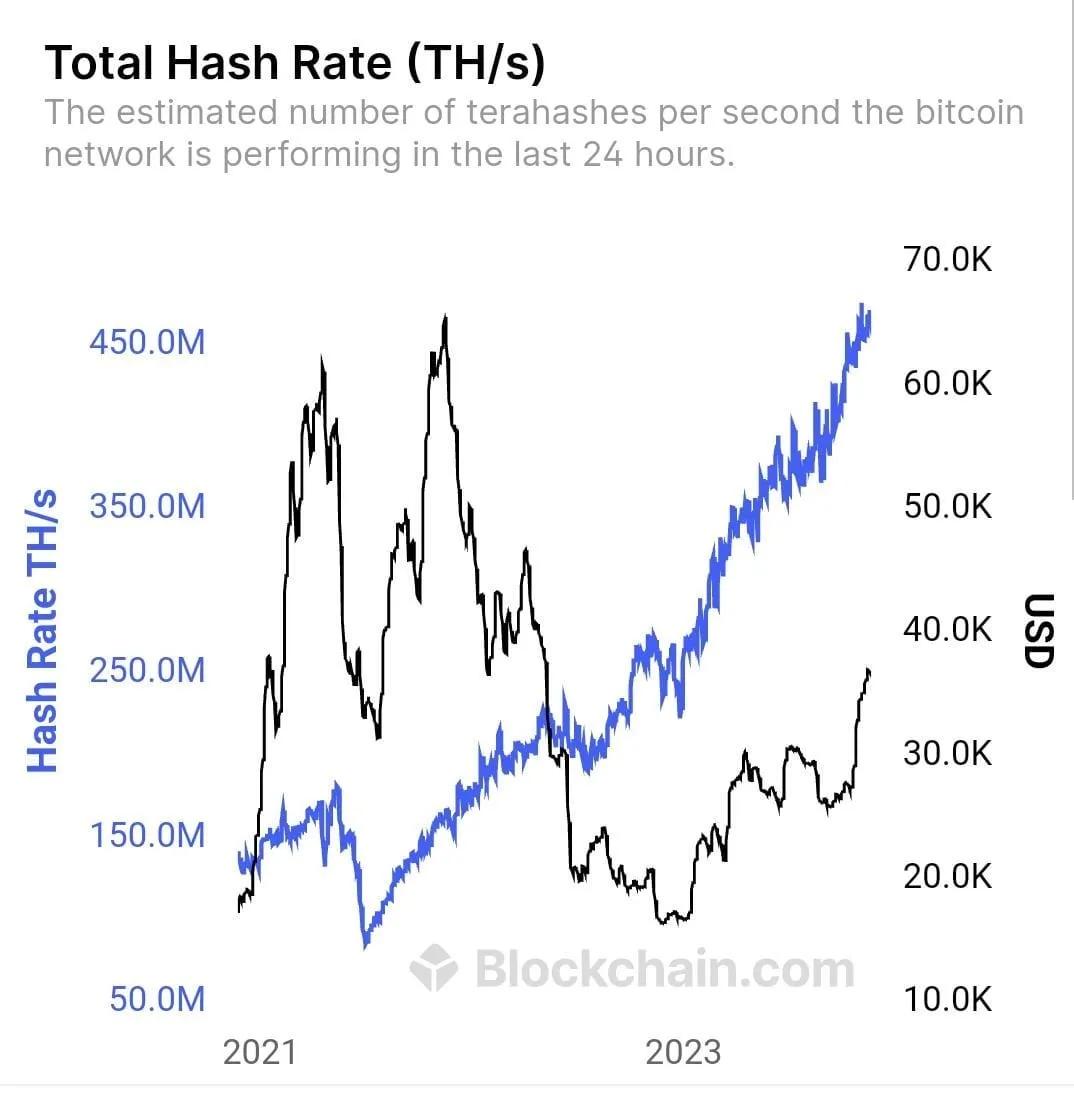

Another important difference. Bitcoin, unlike gold, has an inelastic supply. If the price of bitcoin rises, the incentive to mine more bitcoins is reflected in increased computational power in the form of more hash rates per second, but this does not reflect more bitcoins than expected. This is because the Bitcoin supply has already been pre-programmed by the protocol.

Whatever happens to the price of Bitcoin, the supply will be reduced asymptotically in quadrennial cuts of 50% of the reward per block. These events, called havings, have only happened three times in the history of humanity: on 11/28/12 we went from 50 to 25 per block, on 07/05/16 we went from 25 to 12.5 and on 11/ 05/20 we went from 12.5 to the current 6.25 per block. The next one is scheduled for April next year. At the time of writing, more than 93% of the supply has already been issued. There is 7% left for the rest of the history. Bitcoins, which are already beautiful and rare, will become even rarer. Everything indicates that its beauty will become more expensive to find, given that the hash rate is already triple the hash rate of just three years ago (see below).

Beautiful, isn’t it?